3D-Lab (3D-Digitalisierungslabor)

Short info

The lab addresses digitization of physical objects and the digital reconstruction of collection items. Its method field is visualization, the targetd DH domains are Cultural Heritage and Image Science.- Scanning workflow

- Methods for pattern recognition

- Shape Comparison of artifacts (Ancient portraiture, Greek terracotta figurines, Medieval seals, plaster casts)

- Shape Analysis of artifacts.

- A method for object mining is envisioned.Creating a 3D repository for all collections on campus

Online-Repertorium Archäologischer Objekte:

http://repertorium.uni-goettingen.de

What is the 3D Lab?

Founded in 2016 and headed by Prof. Dr. Martin Langner, the 3D Campus Laboratory of the George August University of Göttingen investigates methods for digitalizing, analyzing, and visualizing cultural assets and objects in collections.

Digital methods are used not only in recording, documenting, and processing data related to images and objects, but also in subsequent analysis, reconstruction, and presentation. The focus is on procedures for image processing, 3D digitalization, and structuring data in databases and collection management systems, quantifying methods and network analysis, pattern recognition and object mining, 3D modeling and visualization, augmented reality, and virtual reconstructions and museums.

The 3D Campus Lab also conducts basic and methodological research. In addition to practical aspects such as the use of established software or the adaptation and further development of specific applications, emphasis is also placed on theoretical depth. In general, we search for suitable procedures for structuring, presenting, and analyzing image and object data and seek to determine which digital tools are useful for describing and interpreting the patterns and processes of historical societies.

Research focuses

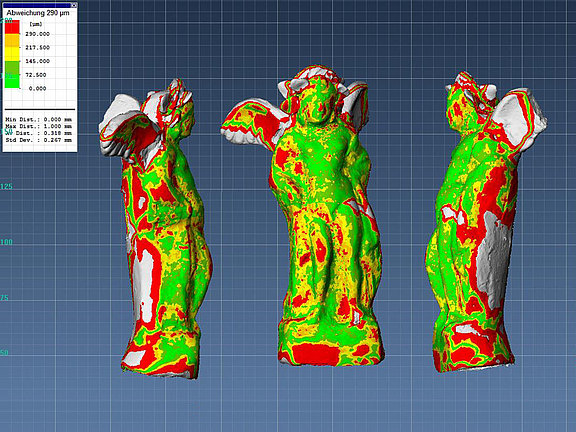

Precise 3D scans of ancient sculptures facilitate, for example, computer-assisted and statistically-based shape comparison and can reveal workshop processes. This can help determine, among other things, whether terracottas were made with the same form. We have also examined how accurately our plaster casts reproduce the cast originals and how closely sculpted architectural ornamentations resemble each other in shape. Roman sculpture worked heavily with copies of Greek originals, and even imperial portraits were produced using a copying process. A more precise comparison of 3D scans now makes it possible to grasp these processes even more accurately and analyze them in terms of the relevant factors of ancient perception.

In addition to precise shape comparisons, an important role is played by the categorization of similarity (and hence culturally shaped concepts of similarity). Archaeologists are faced with the problem that similarities of shape can be asserted verbally, but cannot be adequately described in language. More research using automated 3D shape recognition needs to be conducted into the distinctive differentiation of formal dependencies between similar figures, as elaborated in the field of archaeology. The ‘Schemata’ project aims both to develop procedures for creating corpora automatically by means of 3D pattern recognition (object mining) and to reflect on the related schematizations and their scientific uses for IT and object sciences.

3D models of sculptures can also be used for the virtual reconstruction of lost exhibition contexts. In a collaborative project with the Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, the 494 sculptures comprising the Este collection, which were largely unknown and previously unpublished, are presented virtually as exhibited in 1804 at the Palazzo Catajo near Padua and in 1904 in Vienna in such a way that the differences in spatial effects between the two presentations can be experienced on the computer. These virtual museums also serve as a visual access point to entries in the associated scholarly catalog database.

Documentation: Precise 3D digitalization of objects (here: a plaster cast of the Agias of Delphi) documents the current condition of cultural assets, makes them globally available in repositories, and enables in-depth analysis.

Analysis: Shape comparison (here: two antique teracottas from the same model) helps determine similarity in regard to workshops and trade networks and facilitates object mining and the reconstruction of historical perception.

Presentation: Lost exhibitions (here: the Museo Profano of Tomasso Obizzi circa 1804) can be reconstructed virtually so that they can be experienced once again.